May 6, 2020 7 min read

Robert Mager’s Performance-Based Learning Objectives

Industry:

Solution:

You don’t have to read up on learning objectives for too long before you run into the name of Robert Mager and hear about his performance-based learning objectives. These are also sometimes called three-part learning objectives, behavioral learning objectives, or criteria-based learning objectives.

This isn’t necessarily the only way to write learning objectives. Smart people have continued to think about training and the development of learning objectives since Mager’s time, after all.

But even though there are other schools of thought about learning objectives, what Mager had to say is still solid advice in many cases.

Mager outlines his theory about the best way to create learning objectives in his classic book Preparing Instructional Objectives. You can read our review of Preparing Instructional Objectives if you’re interested, and we highly recommend reading the book, which is informative, quick, and fun. Oh, and here’s a free online version of Mager’s book for you!

Otherwise, here’s the crux of what Mager has to say, below. When you’re done with this article, you might also be interested in our recorded discussion with learning researcher & instructional designer Dr. Patti Shank on Writing Performance-Based Learning Objectives (she calls them “performance objectives” because she focuses so much on job performance).

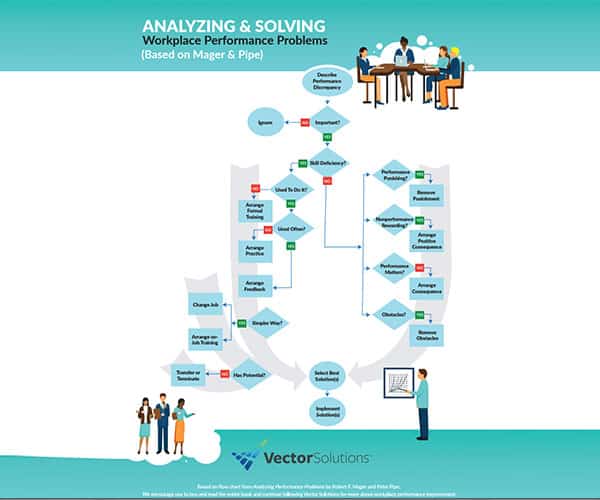

And hey, since you may be here because you’re interested in Robert Mager’s work, and also because people interested in learning objectives may also be interested in performance analysis, don’t forget to check out our article about Robert Mager’s Performance Analysis book and flow-chart, which is one of the seminal works in the field of human performance improvement, or HPI.

Vector EHS Management Software empowers organizations – from global leaders to local businesses – to improve workplace safety and comply with environmental, health, and safety regulations.

Learn more about how our software can save you valuable time and effort in recording, tracking, and analyzing your EHS activities.

Learn more about how we can help:

- Incident Management Software →

- EHS Inspection Software →

- Key Safety Metrics Dashboard →

- Learning Management System (LMS) and Online Training Courses →

- Mobile Risk Communication Platform

Download our EHS Management Software Buyer’s Guide.

The Learner Performs the Objective(s)

First, Mager makes it clear that a learning objective is a statement of “what the learner will be able to perform as a result of some learning experience.” If you pay attention to that, you’ll notice two very important things:

- First, the learning objective states what the learner will be able to do. It’s not a description of the course materials or something that the instructor does. These are two common misconceptions or errors. So if you’re creating job job training materials, your learning objectives are what employees should be able to do when the training is over.

- And second, it’s something the learner performs-some form of action that can be observed and verified. You’ll sometimes hear this stated as something that can be measured.

Those are the truly important aspects of the Mager objective. The rest is all about setting conditions for how the learner can perform the action and how the performance will be evaluated. But let’s step back and look at all three parts of a Mager learning objective. You’ll notice that although we just learned that the learner is the one who’ll be doing this, there’s no part that directly represents the learner, so you’ll have to keep that in mind.

The Three Parts of a Mager Performance-Based Learning Objective

According to Mager, a learning objective should include the following three components:

- A performance (performed by the learner, remember–we just covered that)

- Conditions (under which the learner must perform the performance)

- Criteria (by which the performance is evaluated by another; or, in other words, how well the learner must perform the performance)

Mager admits that in some cases, “it is not always necessary to include the second characteristic, and not always practical to include the third,” but he goes on to say that the more you say about them, the better your objective will communicate. (That point about communicating effectively is one that Mager comes back to again and again in his book, and we’ll come back to it again later in this article as well).

Let’s look at each of those three components in closer detail.

The Performance in the Learning Objective

In Mager’s words, the objective must specify “what learners must be able to DO or PERFORM when they demonstrate mastery of an objective.” So, as we’ve said before, the key is that the learner must do something.

But you’ve got to be careful when you’re writing a learning objective so that you write a performance that you or someone else can somehow observe, and you must tell the learner how their performance will be evaluated. Or, as Mager puts it:

The most important and indispensable characteristic of a useful objective is that it describes the kind of performance that will be accepted as evidence that the learner has mastered the objective.

Because there’s an emphasis on having the learner do something that someone else can observe as evidence, it’s important to avoid learning objectives that include words like “know” and “understand.” Why? Because how can you tell if someone “knows” or “understands” something? Instead, focus on things people really do on their job.

For example, let’s look at the two sample objectives Mager offers as his first quiz of the reader. You’re supposed to pick the correctly written learning objective that includes a performance that someone else can witness or evaluate. Which of the two following learning objectives do you think is better? (Remember, these are directly from Mager’s book.)

- Be able to write a news article.

- Be able to develop an appreciation of music.

If you selected “Be able to write a news article,” you picked the right one. That’s an action that someone can later evaluate and clearly tell if it’s been performed or hasn’t been performed. And it’s clearly something that an employee would have to a on the job–if the employee is a journalist, that is.

On the other hand, how would you know if someone has developed an appreciation of music? What are the clear signs of that–or is that too abstract? Mager would say there’s no clear way to know if someone has developed an appreciation of music.

The Conditions of a Learning Objective

The next thing to do is to state the conditions, if any, in which the learner must complete the performance.

The conditions will tell the leaner things like the following (look for the italicized parts of the objectives below):

- What can I use while doing the performance? (For example: Given 100 toothpicks and some glue, construct a suspension bridge.)

- What will be denied to me? (For example: Perform the multiplication tables up to 20 without the of a calculator.)

- In which conditions will the performance have to occur? (For example: Run a 100-yard dash on a muddy field.)

Remember that Mager said you may not always need to add conditions. As always with Mager, he suggests using them if they make things more clear and remove ambiguity. Mager’s big on being clear and he’s down on ambiguity, and that seems reasonable.

The Criteria of a Learning Objective

Finally, the third part of a Mager three-part, performance-based learning objective is the criterion or criteria. Or, as Mager puts it: “Having described what you want your students to do, you can increase the communication power of an objective by telling them HOW WELL you want them to be able to do it.”

Note again Mager’s focus on “the communication power of an objective.”

Here are some examples (again, look for the italicized parts of the objectives below):

- Identify four out out five product defects on a moving manufacturing line.

- Close ten boxes in a minute.

Mager notes that it may not always be practical to include criteria in a learning objective. When that’s true, don’t include them.

Conclusion: The Learner, the Three Parts, Plus The Communication Power (Clarity, Conciseness, and Lack of Ambiguity) of a Learning Objective

And that’s about it in a nutshell. If you keep in mind that the learning objective states something the learner should do after training, remember to include its three parts, when required–performance, conditions, and criteria–and maximize the communication power of the learning objective to your learner by keeping things clear, concise, and by removing ambiguity, you’ll be headed in the right direction with your learning objectives and creating better training materials that lead to better performance results.

Of course, it couldn’t hurt to buy the book. It’s got a lot of helpful practice exercises and it’s a fun read to boot.

And for even more about learning objectives, feel free to check out any of the articles below:

- What Is a Learning Objective?

- Why Create Learning Objectives?

- The SMART Test for Learning Objectives

- Four-Part ‘ABCD’ Learning Objectives

- Robert Mager’s Performance-Based Learning Objectiveshttps://www.vectorsolutions.com/resources/blogs/how-to-write-smart-learning-objectives/

To learn even more about learning objectives at work, check out our recorded discussion with learning researcher & instructional designer Dr. Patti Shank on Writing Performance-Based Learning Objectives.